Belinda Fox & Neville French: Fall

-

Belinda FoxRenewal, 2022watercolour, ink, pen, collage & acrylic spray on board240 x 260 cm

Belinda FoxRenewal, 2022watercolour, ink, pen, collage & acrylic spray on board240 x 260 cm -

Belinda FoxTransition I (move), 2022watercolour, ink, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board120x 260 cm, 122 x 262 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxTransition I (move), 2022watercolour, ink, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board120x 260 cm, 122 x 262 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxRemnant (grow), 2022watercolour, ink, pen, collage, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board120 x 260 cm, 122 x 262 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxRemnant (grow), 2022watercolour, ink, pen, collage, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board120 x 260 cm, 122 x 262 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar XI (momentum), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, brushed slips, oxide, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)40 x 40 x 34 cm

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar XI (momentum), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, brushed slips, oxide, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)40 x 40 x 34 cm -

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar IX (transition), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, brushed slips, sgraffito, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)38 x 38 x 38 cmSoldIn collaboration with Neville French

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar IX (transition), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, brushed slips, sgraffito, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)38 x 38 x 38 cmSoldIn collaboration with Neville French -

Belinda FoxOne Day II (travel), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxOne Day II (travel), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxTransition II (fall), 2022watercolour, ink, collage, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxTransition II (fall), 2022watercolour, ink, collage, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxOne Day I (alone), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxOne Day I (alone), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxOne Day III (reflect), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxOne Day III (reflect), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board130 x 120 cm, 132 x 122 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxMomentum (spin), 2022watercolour, ink, pen, graphite & spray acrylic on board110 x 100 cm, 112 x 102 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxMomentum (spin), 2022watercolour, ink, pen, graphite & spray acrylic on board110 x 100 cm, 112 x 102 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxOne Day IV (bridge), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board110 x 100 cm, 112 x 102 cm (framed)

Belinda FoxOne Day IV (bridge), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board110 x 100 cm, 112 x 102 cm (framed) -

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar XIII (shelter), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, brushed slips, oxides and sgraffito, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)40 x 37 x 37 cm

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar XIII (shelter), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, brushed slips, oxides and sgraffito, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)40 x 37 x 37 cm -

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar XII (remnant), 2022wheel thrown & altered stoneware, inlaid, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)42 x 39 x 40 cmSold

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar XII (remnant), 2022wheel thrown & altered stoneware, inlaid, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)42 x 39 x 40 cmSold -

Belinda FoxRemnant II (in the depths), 2022watercolour, ink, pen, collage, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board40 x 60 cm, 42 x 62 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxRemnant II (in the depths), 2022watercolour, ink, pen, collage, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board40 x 60 cm, 42 x 62 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxRenewal II, 2022watercolour, ink, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board90 x 140 cm, 92 x 142 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxRenewal II, 2022watercolour, ink, acrylic spray & encaustic wax on board90 x 140 cm, 92 x 142 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda FoxOne Day V (onlooker), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board40 x 60 cm, 42 x 62 cm (framed)Sold

Belinda FoxOne Day V (onlooker), 2022watercolour, ink & encaustic wax on board40 x 60 cm, 42 x 62 cm (framed)Sold -

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar X (nocturne), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, inlaid, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)40 x 46 x 43 cm

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar X (nocturne), 2022wheel thrown & altered porcelain, inlaid, limestone glazes (fired at 1300c)40 x 46 x 43 cm -

Neville FrenchMoon Jar VIII (snow moon), 2022woodfired porcelain wheel thrown & altered, feldspathic & limestone glazes (fired at 1320c)37 x 40 x 40 cmSold

Neville FrenchMoon Jar VIII (snow moon), 2022woodfired porcelain wheel thrown & altered, feldspathic & limestone glazes (fired at 1320c)37 x 40 x 40 cmSold -

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar IV (dislocate), 2021wheel thrown & altered porcelain, inlaid, limestone glazes (fired at 1320c)34 x 33 x 35 cmSoldIn collaboration with Neville French

Belinda Fox & Neville FrenchMoon Jar IV (dislocate), 2021wheel thrown & altered porcelain, inlaid, limestone glazes (fired at 1320c)34 x 33 x 35 cmSoldIn collaboration with Neville French -

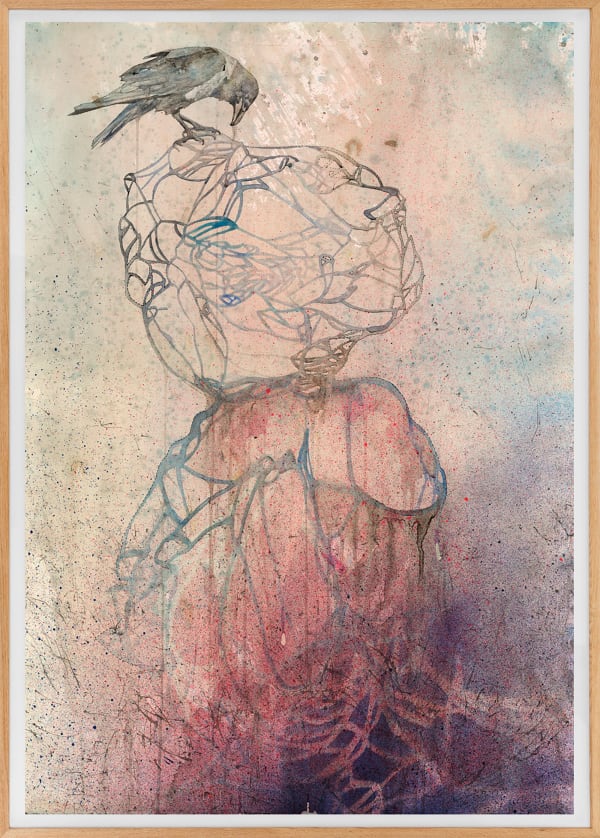

Belinda FoxFollow the Line, 2022digital pigment print139 x 111 cm (framed)Edition of 15 plus 1 artist's proof

Belinda FoxFollow the Line, 2022digital pigment print139 x 111 cm (framed)Edition of 15 plus 1 artist's proof -

Belinda FoxYield, 2022digital pigment print139 x 100 cm (framed)Edition of 15 plus 1 artist's proof

Belinda FoxYield, 2022digital pigment print139 x 100 cm (framed)Edition of 15 plus 1 artist's proof

While Belinda Fox and I were in conversation about this essay, she emailed me the following quote from an interview with British artist Phyllida Barlow, with the postscript, ‘I wish I had said that!’:

I’ve often spoken of the simile being a kind of curse; a desperate need to find a rationale for what we’re looking at. To be abandoned with something that’s only like itself, and refutes definition, is an extraordinary experience. Sculpture can really challenge one in that respect. When the idea is lost, something unknown starts to develop, and this relationship between maker and object is incredibly powerful – it’s as if the work is fighting back. The object that doesn’t yield is a touchstone, giving another dimension to the toughness of life. So, ideas, or thoughts, happen during the process of production, rather than being concrete at the outset and resolved through the making.1

For me, this says a lot about Fox as an artist. While Barlow’s process of discovery and learning, through making, has obvious parallels with Fox’s own practice, the sharing of this text also speaks of her unbounded curiosity and openness to new ideas and influences. In addition, it highlights the ceaseless quest within her work, for the next challenge; the new thing that will push both her and her art forward, into previously unexplored territories.

For Fox, the inspiration for a new body of work often comes at a period of transition or change within her own life – travel, childbirth, upheaval, relocation. The genesis of ‘Fall’ was the artist’s experience of a magical moment in the Netherlands, her then home, just prior to her family’s return to Australia. Riding through the park while taking her daughter to school, she experienced a scene of incredible beauty. The landscape was covered with one of the first falls of snow while the autumn leaves fell gently from the trees, covering the ground in a tapestry of amber and white.

Knowing that this would soon disappear, as the snow melted and turned to mush, made the experience moving and poignant. It spoke powerfully to her of fragility, the difficulty of change, and the extraordinary wonder of nature. The sense of wonder she experienced while witnessing, and somehow being part of the turning of the season, remained emblematic. It is this sense – of stillness, and of everything being poised to change – that she and her long-term collaborator, Neville French, hope to capture in ‘Fall’.

As the natural world and our existence within it is increasingly ravaged by a seemingly endless cycle of droughts, floods and bushfires, the welcome predictability of the changing of the seasons, and the joy that comes with the gentle transition from spring to summer, or autumn to winter, almost seems like a thing of the past. This sense of being on a precipice – a tipping point – of collapse and decay, is central to Fox’s more abstracted paintings, with their evocative washes and elegant web-like forms. Along with the lotus – a symbol of hope and renewal, this motif appears across the artist’s oeuvre; its spindly tendrils seemingly holding everything in place in a careful, but fragile balance. As the artist has said:

... the paintings and ceramics are very much about a deep connection to nature and the fragility of our time. Maybe covid hasn’t helped, and that feeling of ‘just holding on’ or this slow ‘unravelling’ that is in the background of our lives has contributed, but perhaps it’s also that it genuinely feels like it’s so important now to pay attention to our environment. Without a serious ‘present’ mindset we are losing our chance to reverse the damage we have done to our planet.2

In ‘Fall’, abstract paintings such as Transition I (2022) and Transition II (2022) attempt to capture the emotions and feeling of being part of Fox’s ‘magical moment’ in the landscape, but also, importantly, place the viewer at the centre of their mesmerising chaos. If we take the time to stop, to listen to, and to truly feel these works, we come to realise that we are key to the ruinous outcomes that they preface. Yet within the imperfect and transient beauty of ‘Fall’ there is hope – hope that the seasons will continue to turn, and that it isn’t too late to act.

Fox’s long-term collaboration with ceramicist Neville French also embodies this sense of duality – embracing the possibility of potential and failure, while celebrating the joy that exploration of the intrinsic qualities of their shared materials and processes can bring to the maker. In ‘Fall’, French has concentrated on the form of the iconic Korean moon jar, made during the Choson dynasty (1392–1910) and celebrated in the 20th century for the subtle imperfections of its shape and surface. Traditionally made in white porcelain and created by joining two bowls together, the form of the moon jar resonated with both the concept and practice of collaboration and Fox’s relatively recent return from the Netherlands.3

Indeed, when contemporary Korean ceramicist Young Sook Park describes the moon jar, she could well be speaking of the pairs’ collaborative process: “A perfect union happens when the top and the bottom surrender their individual selves and reach a compromise to exist forever as 'one'.” 4 The coming together of painter and ceramicist is the ultimate act of trust and respect. French makes the forms and then hands them over to Fox, who paints upon them with a range of clay slips and works into their pristine surfaces with a variety of tools. They are then glazed by French.

Drawing on his extensive material knowledge and experience, French set about creating a series of moon jars which have deliberately cracked, or ‘failed’. In effect an ‘unlearning’ of everything he has strived for over his long career, these vessels are at once beautiful and compelling, caught as they are, in various stages of slumping and rupture. While cracks in ceramic forms are largely regarded as faults and something to be avoided at all costs, the artist’s approach to these broken forms draws upon the reverence accorded the water jars made for the Zen Buddhist tea ceremony in Japan in the 16th century and for the high value afforded to each vessel for its unique cracked flaw.5 From the Fontana like slash of Snow Moon (2022) to the gaping hole and shards of Shelter (2022), the traditional form of the moon jar is knowingly pushed to its limits. French’s technical expertise and knowledge can encourage certain outcomes in the kiln, but in the end, he must ultimately relinquish control.

Within the complementary forms and mark-making of the paintings and ceramics in ‘Fall’, the viewer is encouraged to pause and take time and to experience a precious moment of stillness. Inspired by the artists’ shared interest in the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi and the inspiration they draw from nature, the works speak of the passing of time, of the challenges and rewards of transformation and of the beauty and fragility of the natural world.

Kelly Gellatly

Curator, Writer & Arts Advocate

Founding Director of Agency Untitled

-

Phyllida Barlow in From the sculptor’s studio, by Ina Cole 2021, pp. 20-33. Belinda Fox, email to the author, 11 June 2022

-

Belinda Fox, email to the author, 13 June 2022

-

Neville French, “Some quick notes on the fractured moon jars”, email to the author, 5 July 2022

-

“The 'Moon Jar': A Transcendent Ceramic Form”, accessed 7 July 2022.

-

Neville French, “Some quick notes on the fractured moon jars”, email to the author, 5 July 2022