Joshua Yeldham: Providence

-

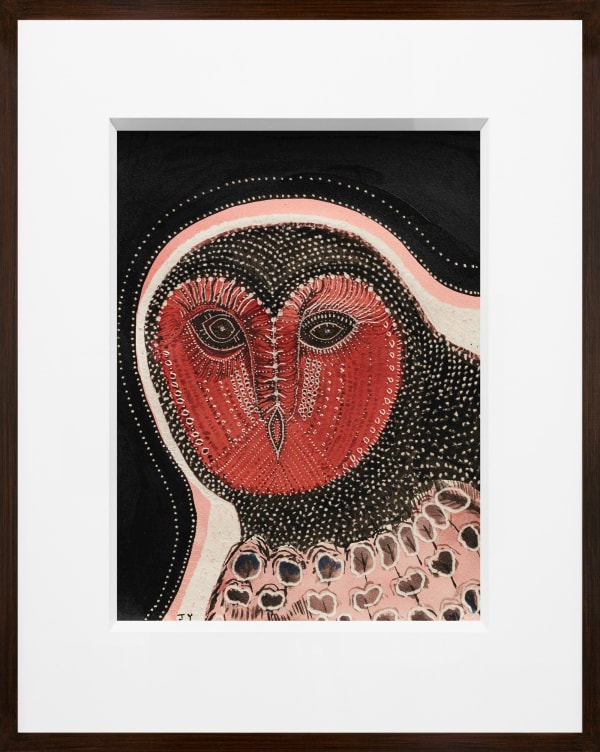

Joshua YeldhamAgni Kyoto Owl (Artist Edition), 2015acrylic on hand-carved pigment print120 x 100 cm, 131 x 111 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAgni Kyoto Owl (Artist Edition), 2015acrylic on hand-carved pigment print120 x 100 cm, 131 x 111 cm (framed) -

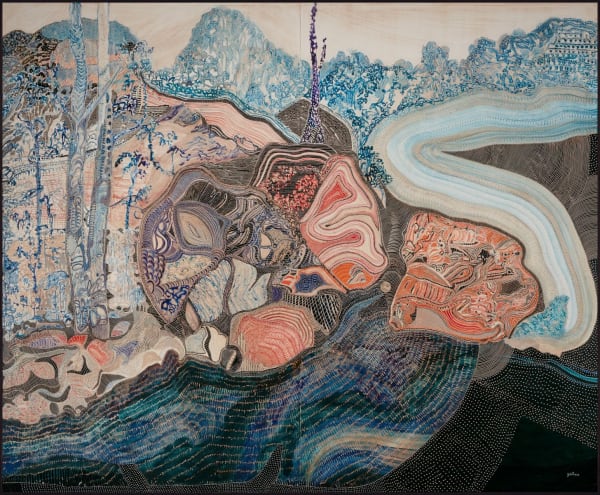

Joshua YeldhamAngophora – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board204 x 152 cm, 210 x 158.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAngophora – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board204 x 152 cm, 210 x 158.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree I (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print100 x 100 cm, 110.5 x 110.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree I (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print100 x 100 cm, 110.5 x 110.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree II (Ed. of 10), 2020hand-carved pigment print130 x 195 cm, 140.5 x 205 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree II (Ed. of 10), 2020hand-carved pigment print130 x 195 cm, 140.5 x 205 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree III (Ed. of 10), 2020hand-carved pigment print120 x 120 cm, 130 x 130 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree III (Ed. of 10), 2020hand-carved pigment print120 x 120 cm, 130 x 130 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree IV (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print36 x 36 cm, 62 x 60 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree IV (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print36 x 36 cm, 62 x 60 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree V (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print40 x 40 cm, 62 x 60 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree V (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print40 x 40 cm, 62 x 60 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree VI (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print40 x 40 cm, 62 x 60 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamAspen Tree VI (Ed. of 10), 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print40 x 40 cm, 62 x 60 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamBelow the Midden , 2020acrylic on hand-carved board47 x 36 cm, 54.5 x 44.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamBelow the Midden , 2020acrylic on hand-carved board47 x 36 cm, 54.5 x 44.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamBird of Protection, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved cedar55.5 x 35.5 cm, 42 x 22 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamBird of Protection, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved cedar55.5 x 35.5 cm, 42 x 22 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamBlack Moon Owl, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board in antique sieve frame52 x 52 cm

Joshua YeldhamBlack Moon Owl, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board in antique sieve frame52 x 52 cm -

Joshua YeldhamBlue Coral, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamBlue Coral, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamBlue Hawkesbury, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper100 x 117 cm, 110 x 129 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamBlue Hawkesbury, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper100 x 117 cm, 110 x 129 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamBlue Water Owl, 2020acrylic, ink & cane on hand-carved paper on cedar46 x 46 cm, 56 x 55.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamBlue Water Owl, 2020acrylic, ink & cane on hand-carved paper on cedar46 x 46 cm, 56 x 55.5 cm (framed) -

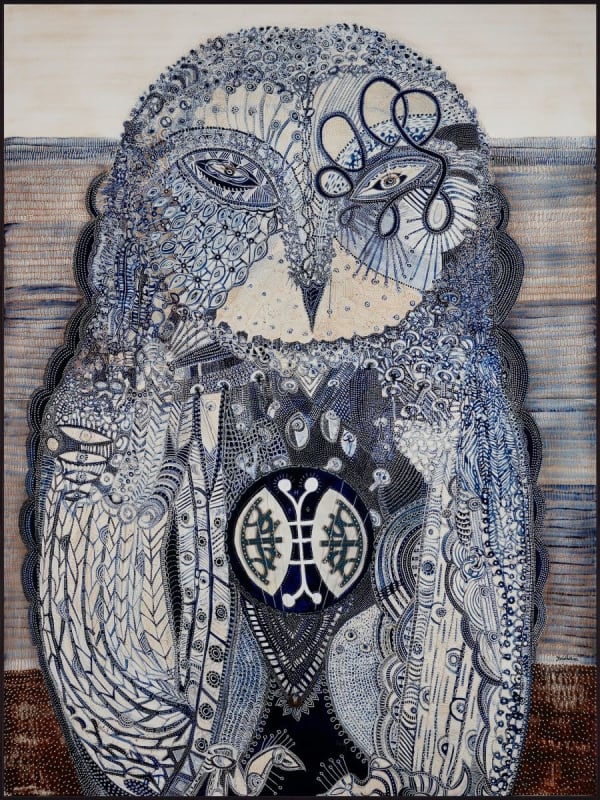

Joshua YeldhamBoobook, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 208 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamBoobook, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 208 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamCentre Pool – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board36 x 46 cm, 44.5 x 54.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamCentre Pool – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board36 x 46 cm, 44.5 x 54.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamCharcoal Wood – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board152 x 203 cm, 159 x 210 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamCharcoal Wood – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board152 x 203 cm, 159 x 210 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamDriftwood – Lord Howe Island, 2020unique hand-carved pigment print144 x 150 cm, 154 x 160 cm (framed)Edition of 10

Joshua YeldhamDriftwood – Lord Howe Island, 2020unique hand-carved pigment print144 x 150 cm, 154 x 160 cm (framed)Edition of 10 -

Joshua YeldhamEndurance – Mt Cook (Ed. of 10), 2020hand-carved pigment print150 x 150 cm, 160 x 160 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamEndurance – Mt Cook (Ed. of 10), 2020hand-carved pigment print150 x 150 cm, 160 x 160 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamEndurance – Smiths Creek, 2015unique hand-carved pigment print140 x 120 cm, 167 x 145 cm (framed)Edition of 28

Joshua YeldhamEndurance – Smiths Creek, 2015unique hand-carved pigment print140 x 120 cm, 167 x 145 cm (framed)Edition of 28 -

Joshua YeldhamEye of the Beholder, 2020acrylic and charcoal on unique hand-carved pigment print149 x 90 cm, 160 x 100 cm (framed)Edition of 10

Joshua YeldhamEye of the Beholder, 2020acrylic and charcoal on unique hand-carved pigment print149 x 90 cm, 160 x 100 cm (framed)Edition of 10 -

Joshua YeldhamFertility Owl, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamFertility Owl, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed) -

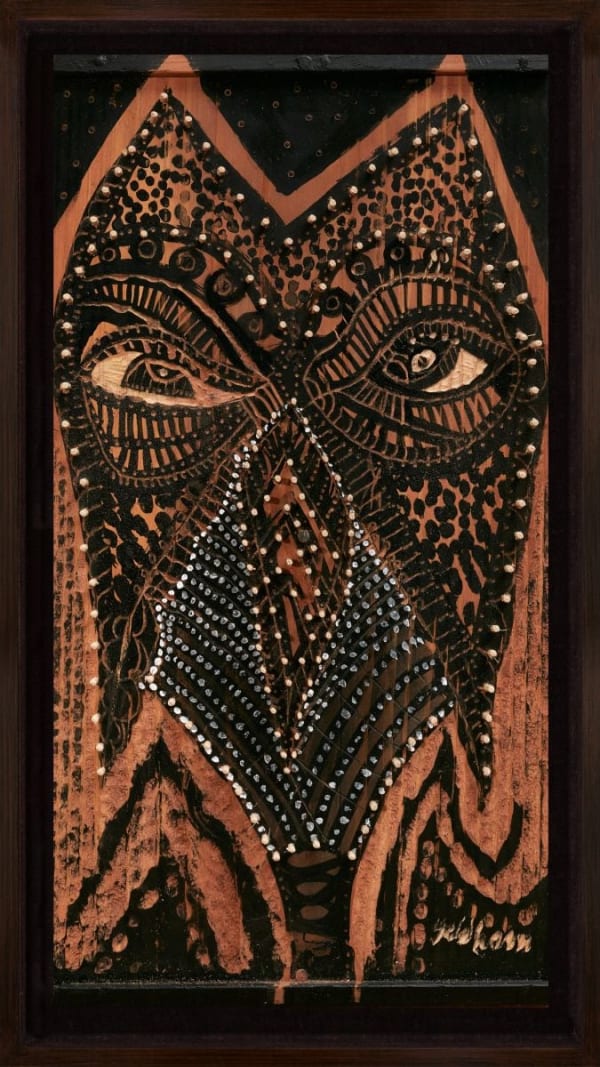

Joshua YeldhamHawkesbury River Owl, 2020acrylic, cane & instrument on hand-carved board203 x 152 cm, 205 x 154 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamHawkesbury River Owl, 2020acrylic, cane & instrument on hand-carved board203 x 152 cm, 205 x 154 cm (framed) -

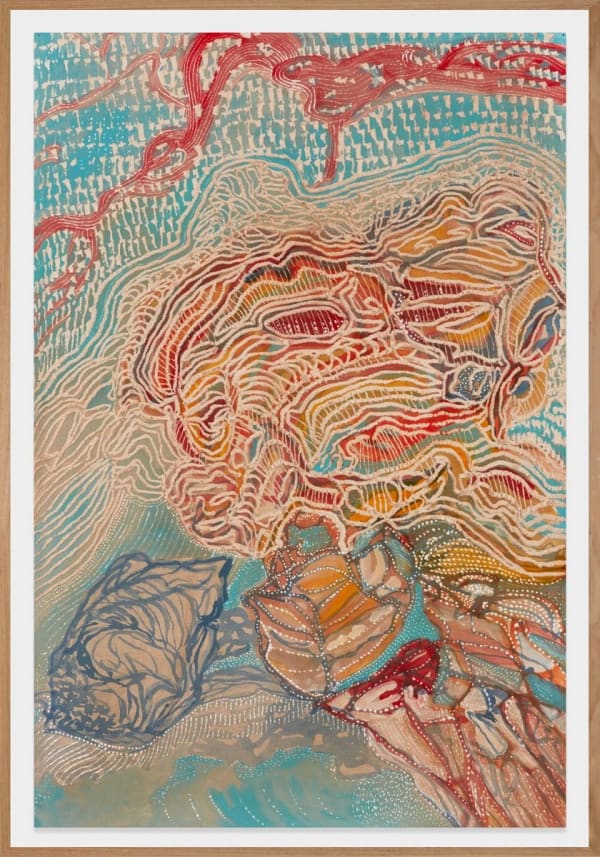

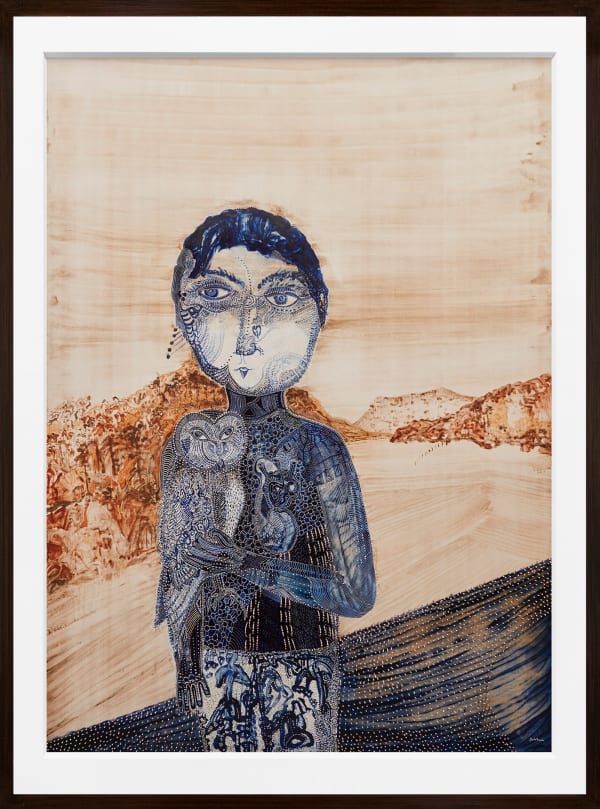

Joshua YeldhamHolding my Father's Heart, 2020unique hand-carved pigment print181 x 141 cm (framed)Edition of 28

Joshua YeldhamHolding my Father's Heart, 2020unique hand-carved pigment print181 x 141 cm (framed)Edition of 28 -

Joshua YeldhamJude (Ed. of 9), 2013hand-carved pigment print160 x 150 cm, 170 x 160 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamJude (Ed. of 9), 2013hand-carved pigment print160 x 150 cm, 170 x 160 cm (framed) -

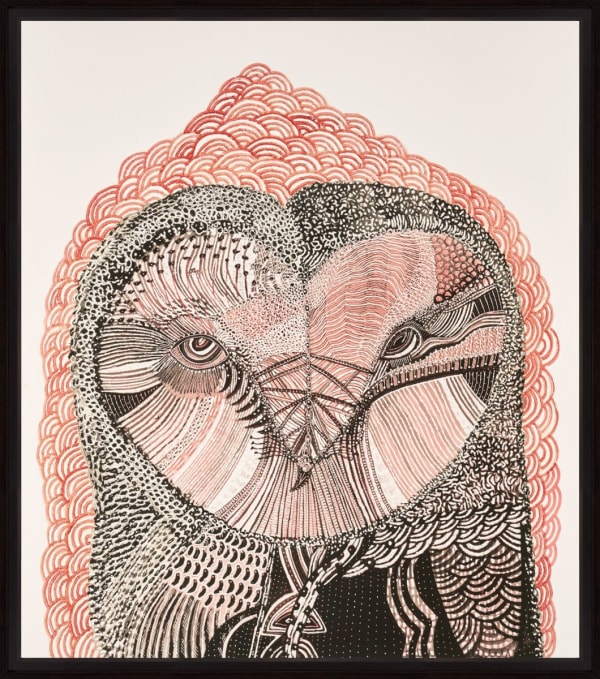

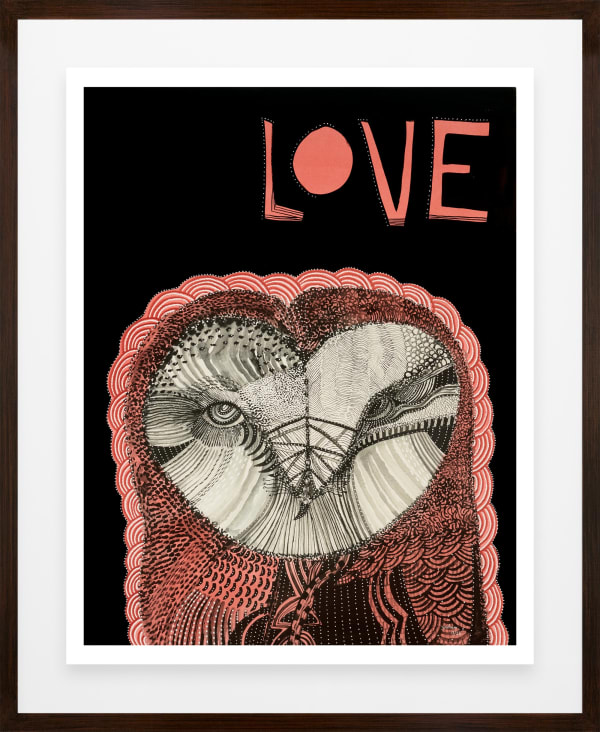

Joshua YeldhamKyoto Love Owl (large), 2017unique hand-carved pigment print100 x 77 cm, 120.5 x 96 cm (framed)Edition of 35

Joshua YeldhamKyoto Love Owl (large), 2017unique hand-carved pigment print100 x 77 cm, 120.5 x 96 cm (framed)Edition of 35 -

Joshua YeldhamLilly Owl, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamLilly Owl, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamLittle Lord Howe, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board30 x 23 cm, 41.5 x 34 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamLittle Lord Howe, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board30 x 23 cm, 41.5 x 34 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMangrove Song, 2020musical assemblage226 x 145 x 26 cm

Joshua YeldhamMangrove Song, 2020musical assemblage226 x 145 x 26 cm -

Joshua YeldhamMelody Owl, 2020acrylic, cane & instrument on hand-carved board203 x 152 cm, 205 x 154 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMelody Owl, 2020acrylic, cane & instrument on hand-carved board203 x 152 cm, 205 x 154 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMidnight Waterhole, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 208 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMidnight Waterhole, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 208 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMonstera Deliciosa Owl, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board204 x 152 cm, 210 x 159 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMonstera Deliciosa Owl, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board204 x 152 cm, 210 x 159 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMoon Taro – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper120 x 102 cm, 130 x 114 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMoon Taro – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper120 x 102 cm, 130 x 114 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMountain Spring – Mt Gower, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper153 x 57 cm, 163 x 69 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMountain Spring – Mt Gower, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper153 x 57 cm, 163 x 69 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMt Gower – Blue Cove, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper102 x 120 cm, 114 x 130 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMt Gower – Blue Cove, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper102 x 120 cm, 114 x 130 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMt Gower – Little Owl Cove, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper102 x 120 cm, 114 x 130 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMt Gower – Little Owl Cove, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper102 x 120 cm, 114 x 130 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamMt Gower – Lord Howe Island, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 220 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamMt Gower – Lord Howe Island, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 220 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Black Bamboo – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic & cane on hand paper on board40 x 30 cm, 53 x 43 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Black Bamboo – Yeomans Bay, 2020acrylic & cane on hand paper on board40 x 30 cm, 53 x 43 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Black Mountain, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board35.5 x 45.5 cm, 49.5 x 58.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Black Mountain, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board35.5 x 45.5 cm, 49.5 x 58.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Black Taro, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Black Taro, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Castle Bay, 2014unique hand-carved pigment print48 x 35 cm, 70 x 58 cm (framed)Edition of 28

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Castle Bay, 2014unique hand-carved pigment print48 x 35 cm, 70 x 58 cm (framed)Edition of 28 -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Smiths Creek (Ed. of 9), 2020acrylic on hand-carved sand cast stone, mounted on hand-carved pigment print with cane on Dibond150 x 275 cm, 150.5 x 276 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of Smiths Creek (Ed. of 9), 2020acrylic on hand-carved sand cast stone, mounted on hand-carved pigment print with cane on Dibond150 x 275 cm, 150.5 x 276 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the Battlefield, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board201 x 150 cm, 210 x 159 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the Battlefield, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board201 x 150 cm, 210 x 159 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the Blue Heart, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the Blue Heart, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the Kyoto Moon (Artist Edition), 2015acrylic on hand-carved pigment print112 x 100 cm, 133 x 120 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the Kyoto Moon (Artist Edition), 2015acrylic on hand-carved pigment print112 x 100 cm, 133 x 120 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the River Bend, 2020acrylic on hand-carved wood45 x 45 cm, 51.5 x 51.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamOwl of the River Bend, 2020acrylic on hand-carved wood45 x 45 cm, 51.5 x 51.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamOyster Owl – Satellite Island, 2019unique hand-carved pigment print81 x 61 cm, 103 x 82 cm (framed)Edition of 28

Joshua YeldhamOyster Owl – Satellite Island, 2019unique hand-carved pigment print81 x 61 cm, 103 x 82 cm (framed)Edition of 28 -

Joshua YeldhamPhantom Limb – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board204 x 153 cm, 210 x 158.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamPhantom Limb – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board204 x 153 cm, 210 x 158.5 cm (framed) -

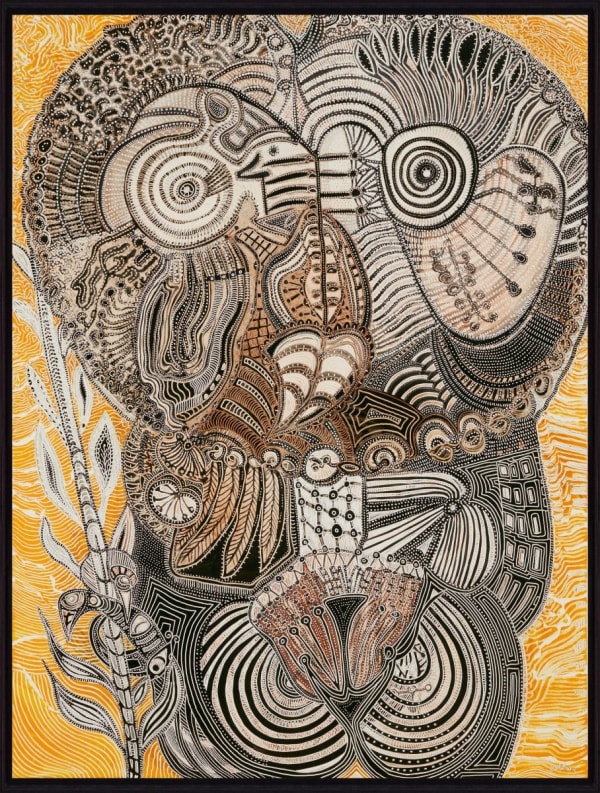

Joshua YeldhamProvidence, 2020acrylic, cane & instrument on hand-carved board200 x 244 cm, 202 x 246 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamProvidence, 2020acrylic, cane & instrument on hand-carved board200 x 244 cm, 202 x 246 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamRed Wood Owl – Colo River, 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print84 x 48 x 20 cm

Joshua YeldhamRed Wood Owl – Colo River, 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print84 x 48 x 20 cm -

Joshua YeldhamRiver Bend, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board40 x 40 cm, 53 x 53 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamRiver Bend, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board40 x 40 cm, 53 x 53 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamRivers Edge – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print on canvas on board62 x 82 cm, 64.5 x 84.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamRivers Edge – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic on hand-carved pigment print on canvas on board62 x 82 cm, 64.5 x 84.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamSea Eagle and Man, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board126 x 110 cm, 132 x 117 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamSea Eagle and Man, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board126 x 110 cm, 132 x 117 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamSnake Knowledge – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 208 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamSnake Knowledge – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic on hand-carved linen paper200 x 200 cm, 208 x 208 cm (framed) -

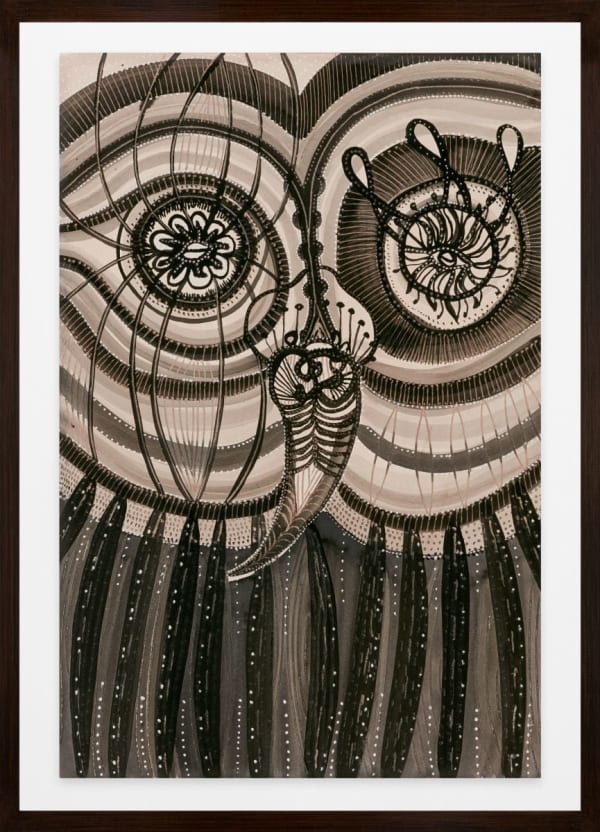

Joshua YeldhamSooty Owl (Ed. of 25), 2019hand-carved pigment print156 x 122 cm, 156 x 122 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamSooty Owl (Ed. of 25), 2019hand-carved pigment print156 x 122 cm, 156 x 122 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamSpirit Owl, 2018unique hand-carved pigment print90 x 90 cm, 115 x 113 cm (framed)Edition of 30

Joshua YeldhamSpirit Owl, 2018unique hand-carved pigment print90 x 90 cm, 115 x 113 cm (framed)Edition of 30 -

Joshua YeldhamStart Small – Grow Tall (Original Master), 2015acrylic on hand-carved pigment print100 x 94 cm, 111 x 98 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamStart Small – Grow Tall (Original Master), 2015acrylic on hand-carved pigment print100 x 94 cm, 111 x 98 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamSummer Owl, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board121 x 91 cm, 128 x 97.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamSummer Owl, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board121 x 91 cm, 128 x 97.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamSurya (Sun) Owl, 2019unique hand-carved pigment print48 x 36 cm, 70 x 58 cm (framed)Edition of 28

Joshua YeldhamSurya (Sun) Owl, 2019unique hand-carved pigment print48 x 36 cm, 70 x 58 cm (framed)Edition of 28 -

Joshua YeldhamTaro, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved cedar46.5 x 23.5 cm, 59 x 36.5 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamTaro, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved cedar46.5 x 23.5 cm, 59 x 36.5 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamThe Owl of Lord Howe, 2020unique hand-carved pigment print150 x 120 cm, 160 x 130 cm (framed)Edition of 35

Joshua YeldhamThe Owl of Lord Howe, 2020unique hand-carved pigment print150 x 120 cm, 160 x 130 cm (framed)Edition of 35 -

Joshua YeldhamWaterfall – Mt Gower, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board30.5 x 23 cm, 41.5 x 34 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamWaterfall – Mt Gower, 2020acrylic on hand-carved board30.5 x 23 cm, 41.5 x 34 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamWhite Rock – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamWhite Rock – Smiths Creek, 2020acrylic on hand-carved paper board76 x 51 cm, 84.5 x 68 cm (framed) -

Joshua YeldhamYeomans Bay – Bird Rock, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board200 x 244 cm, 202 x 246 cm (framed)

Joshua YeldhamYeomans Bay – Bird Rock, 2020acrylic & cane on hand-carved board200 x 244 cm, 202 x 246 cm (framed)

Providence, one meaning of the word is good fortune. Another is nature’s ability to yield an abundance of spiritual solace. In Joshua Yeldham’s garden there is a tree. It’s hanging roots and trunk are like a carved curtain. It’s fronds loop and dance into the light. The tree looks archaic and yet it is only sixteen winters old. Steeped in shadow, the tree provides.

Some might see this wild planting as an arbour for nests. Others will wish for enough wood to build an Ark. But for this artist the tree is being harvested both within and without. It is planted in the soil outside his window and upon the thirsty paper quenched by ink. It bends sideways and enters his house, uprooting symmetry, curling around mountains and probing the mangrove mud. Incarnated on canvas the tree is swollen, a growing blessing. It is also intricate and unpredictable. Insects tattoo its branches and claws scratch its skin. The oblique geometry of the tree curves like a river. Its’ nocturnal life is secret. Like the paintings that whisper to one another in the artist’s studio at night; the tree does not sleep.

Yeldham is alive to primal complicity. He seems to study each hollow and root network until it forms human veins and heart chambers. His carved drawings awaken and unfurl their lines like fern fronds. The paintings have the power to engulf you. So much so that you want to walk inside their paths and run your hands over their ridged skins like soft dry bark.

Yeldham planted a tree and grew a language beyond landscape conventions. From his earliest paintings made in the Strzelecki desert, he saw the tree not as a visual convenience to create scale or context but as a complete cosmos within itself. “People need to immerse and not objectify,” he said simply. And as a result his artworks became larger and more enveloping over time.

These are elaborate offerings. The ornamentation on their surface works like a map to a place you already inhabit. And the time the artist takes to paint, draw, carve, sculpt and glaze each piece is rewarded by the time it deserves to know them: To interlock with the vibrational hum between positive and negative space or just stare at a feather. When you are close to these works you want to lay your hands upon their furrows and perhaps even lean in, just the same way we place our body on the skin of a forest elder. To touch and to listen. To be hold and be held.

Some of the more monochrome pieces in this series feature expanses of contemplative space. White and black are used in a deeply meditative almost minimal way. But many more are full to bursting. Brimming with an ambition to expand on a kinetic path of germination. As a counterpoint to all the minutae, massive owls and curving rivers calm the eye. They also help us to anchor somewhere in the rushing tide of lines. Because Yeldham does paint, draw and sculpt in a torrent.

This is an artist who pays homage through detail. Limitless nature is reflected by infinite reply. To reach this point, his surfaces gain depth through a gradual accretion of marks. Dragging lines forward and then peeling them back, staining and then erasing with the drill tip: each painting becomes a palimpsest for the sky, the water and the earth.

Almost all of his works begin with calligraphy, often drawn in the terrains he loves: The Hawkesbury River, Mt. Cooke in New Zealand, Lord Howe Island. The artworks that break with this pattern are his photographs, taken with a phone camera and exploded to life size or larger. The photographs for this exhibition were taken in the mountains of Colorado. He looked at the trees and after a time he noticed the trees looking back at him:

“When I was in the forest I was struck by the eyes of the fallen limbs, hundreds of eyes inside the broken sockets of branches and in the hollows of the trees. Over eight days of walking I had a strong feeling of nature’s intelligence. It was her watching me rather than me casting my gaze over the landscape.”

In conversation with this moment, Yeldham returned to the studio and carved eyes into the tree trunks. The eye, in his view, is both a portal and a primal key to survival. Forests are vulnerable to predators; they live in a constant state of vigil. In this rare instance the artist uses personification to share his point. Framed by the pale void of the snow, a tree sheds tears that look like seed pearls. She appears bejewelled. In some ways this is a strange thing for an Animist to do. You cannot ‘add’ to nature. But these tiny carvings upon the tree are not possessive. The artist is not marking territory or merely adding extra optical depth. Joshua Yeldham has been holding this dialogue for a long time. The trees know him. “It is adornment” he says “and it is reverence.”

Anna Johnson

Art Writer